Places

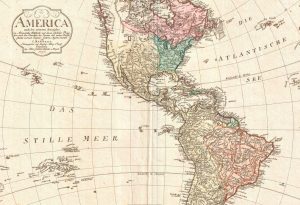

The Spanish were the first Europeans to permanently settle in the Americas. A map of 18th century North America shows the sweeping expanse of the Spanish empire, from the fortress of San Augustín, Florida — founded in 1565 before Jamestown, Virginia — to the small outpost of San Francisco started in the desolate wilderness of Alta California in 1776. The Spanish settled the southwestern United States in the 16th century, formally establishing Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1610.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to permanently settle in the Americas. A map of 18th century North America shows the sweeping expanse of the Spanish empire, from the fortress of San Augustín, Florida — founded in 1565 before Jamestown, Virginia — to the small outpost of San Francisco started in the desolate wilderness of Alta California in 1776. The Spanish settled the southwestern United States in the 16th century, formally establishing Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1610.

Spanish explorers traveled further north along the Pacific Coast to Canada in 1774 and by the late 1700s had established a military post on Vancouver Island, 350 miles north of Seattle. The Spanish sailed from the Caribbean to the Chesapeake Bay in 1526, then called the Bahía de Santa María, about 80 years before the romanticized English encounter with Pocahontas. In the 1520’s Spanish navigators also explored as far north as Cape Cod, Massachusetts and Bangor, Maine. As part of the peace negotiations after the Seven Years War in 1762, the French ceded New Orleans and the Mississippi territories to the Spanish.

This historic presence throughout North America is reflected in a number of the key events in the American Revolution in which the Spanish and Hispanic Americans participated. Spanish merchants followed their long-established trade lines from Bilbao in northern Spain to ship supplies for the war to the New England ports. General Charles Lee of the Continental Army sent soldiers to Spanish-owned New Orleans in 1776 to request military supplies from the Spanish Governor, which were given to the American Cause.

In 1776, the Spanish began shipping gunpowder from factories in Mexico through New Orleans to the North American Continental Army. In Madrid, King Carlos III funded half of the company, Rodrigue Hortalez et Cie, with his nephew, the French King, sending thousands of uniforms, guns, cannons and other supplies to the Continental Army during the earliest days of the War. Strategic military supplies were shipped from Spain, some sent directly to the New England coast and others warehoused for shipment from Havana, Cuba.

To raise money for their own war against the British that began in 1779, King Carlos III levied a specific tax throughout the Spanish American empire, paid by Spanish and Hispanic Americans from California to New Mexico. The Spanish and Hispanic Americans fought battles from Pensacola, Florida, to San Carlos, Nicaragua. These battles diverted British soldiers, equipment and supplies that would have been used against the North Americans.

As the Revolution entered its seventh long year, the situation was desperate. The unpaid and undersupplied soldiers of the North American Army rioted and mutinied. The hyper-inflated Continental dollar completely collapsed in the spring. The North Americans were wearying of the rebellion against one of the most powerful empires in the world.

George Washington and his staff prepared for what many believed would be the last opportunity to fight with French military assistance at the Battle of Yorktown, Virginia. The supplies and payroll for this crucial victory were financial by a last minute collection from the citizens of Havana. These financiers and merchants lent silver pesos and gold coins, much of which originated in the mines at Guanajuato and Zacatecas, Mexico.